Understanding Helicopter Parenting

In this article

The defining characteristic of a helicopter is its ability to hover. This is done by staying in motionless flight above a reference point. The visual can also be used to think about an overbearing parent – the helicopter is the caregiver, and the reference point is the child.

As the parent hovers, they may lose sight of their own identity and direction – and the child may feel smothered, overwhelmed, or blocked from living their own life and learning from their mistakes.

What is helicopter parenting?

The term helicopter parent was first introduced in 1990 in a book titled “Parenting Teens with Love & Logic.” In the book, the authors described helicopter parents as those who hover around their children, ready to sweep in and rescue them from disappointments and painful experiences.

They went on to explain that helicopter parents behave this way because “they confuse love, protection, and caring” with not allowing their child to fail.

A helicopter parent will micromanage and entwine themselves in all aspects of their child’s life. In the process, they may communicate the attitude that the child is:

- Incapable of managing even developmentally appropriate tasks

- Unable to overcome their own struggles

- In need of constant protection from the dangers of the world

What are the signs of a helicopter parent?

More than a helping hand or secure base, helicopter parents take parental involvement to the extreme. [1] Jeong, J., Franchett, E., De Oliveira, C. V. R., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021). Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 18(5), e1003602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602 This can happen during infancy, childhood, and even into college age and beyond. [2] Kouros, C. D., Pruitt, M. M., Ekas, N. V., Kiriaki, R., & Sunderland, M. (2016). Helicopter parenting, autonomy support, and college students’ mental health and well-being: the moderating role of sex and ethnicity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0614-3

Examples of helicopter parenting include:

- Completing your child’s homework

- Doing basic chores such as cleaning up toys or making your child’s bed even after it would be developmentally appropriate for them to do so

- Arguing with or complaining to your child’s teachers, friends, and coaches whenever there is conflict

- Ignoring your own activities and interests in favor of your child’s schedule

- Overscheduling your child to give them a competitive advantage

The Helicopter Parenting Behaviors Questionnaire used in research to study the effects of controlling parenting includes items such as:

- “My parent regularly wants me to call or text her to let her know where I am”

- “My parent monitors my exercise schedule”

- “If I were to receive a low grade that I felt was unfair, my parents would call the professor”

Another section of the scale explores a parent-child relationship that promotes autonomy – the reverse of helicopter parenting. Examples include:

“My parent encourages me to choose my own classes”

“My parent encourages me to make my own decisions and take responsibility for the choices I make”

The psychology behind helicopter parenting – why some parents hover

There are myriad reasons why a parent may become overprotective, such as following what they’ve been taught by role models or responding to a stressor such as a child’s illness.

Let’s explore a couple of pathways to helicopter parenting in more depth.

Attachment parenting gone too far

In the 1930s, psychiatrist John Bowlby developed a theory that babies form a “small hierarchy of attachments.” Nearly two decades later, Mary Ainsworth joined Bowlby and later described relational patterns between children and their mothers based on how the children responded to separations and reunions.

When babies have a secure attachment, they explore freely from the “secure base” of their parents. Caregivers who foster a secure attachment are responsive, warm, loving, and emotionally available.

In this environment, children are able to express their positive and negative feelings and develop fewer defenses against challenging emotions.

A secure attachment can also:

- Offer a sense of safety and security

- Support emotion regulation

- Provide a secure base from which to explore

When it comes to promoting a secure attachment, it’s less about what the parent specifically does and more about their attunement to the child, engagement as a parent, and emotional state. For example, a parent can check all the boxes and do all the right things, but stressed, checked out, or ignoring the baby’s signals will fail to support a secure attachment.

In this way, well-meaning parents can overdo it, trying to meet their child’s every need, and in the process, turn into helicopter parents.

Confronting the dangers of racism and discrimination

Rather than multiplying privileges and advantages, as is the goal for many helicopter parents, raising children of color may require extra hovering to ensure a child’s safety.

Racism and discrimination can put a child in immediate danger and also have long-term health impacts. [3] How racism can Affect Child Development – Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2023, September 20). Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/racism-and-ecd/

In addition to issues of physical and psychological safety, BIPOC children, on the whole, have less social mobility, are more harshly disciplined in school (even daycare), and are more likely to be charged with a crime. [4] Badger, E., Miller, C. C., Pearce, A., & Quealy, K. (2018, March 27). Extensive data shows punishing reach of racism for Black boys. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/race-class-white-and-black-men These issues of structural racism are most pronounced among Black boys.

Therefore, speaking to adults who are treating your child unfairly, being selective about the schools they attend, or monitoring who your child is spending time with can be some of the realities of raising a child of color.

– Kate Dubé, Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW)

The effects of helicopter parenting on children

Helicopter moms and dads aim to prevent their children from failing, yet ironically, their hovering behavior may actually undermine their children’s well-being.

While the effects of helicopter parenting are likely dependent on cultural context, overall research points towards negative effects on the child, such as:

- Heightened sense of entitlement

- Higher incidence of drug use

- Increased levels of anxiety and depression

- Ineffective coping skills

- Decreased emotional regulation

- Lower academic performance

- Poor self-confidence

- Less resilience [5] Arlinghaus, K. R., Hahn, S. L., Larson, N., Eisenberg, M. E., Berge, J. M., & Neumark‐Sztainer, D. (2023). Helicopter Parenting Among Socio-Economically and Ethnically/Racially Diverse Emerging Adults: Associations with Weight-Related Behaviors. Emerging Adulthood, 11(4), 909–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968231171317

The Western, individualistic model of self-determination theory also supports the idea that helicopter parenting can be harmful. In this framework, humans have three basic and innate needs, which include:

- Autonomy – or the ability to make your own choices

- Competence – or feeling confident in your abilities and accomplishments

- Relatedness – or feeling connected and supported by caring relationships [6] Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

Following this model, there are certain aspects of development that an overly protected child may miss. In this way, the effects of helicopter parenting may also seep into adulthood.

Are there any pros of helicopter parenting?

Research and opinions are mixed, and some say that helicopter parenting works to improve academic performance, health, and self-esteem. [7] Druckerman, P. (2019, May 21). Opinion | The bad news about helicopter parenting: It works. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/opinion/helicopter-parents-economy

However, even these proponents of hands-on parenting stipulate that “authoritarian” parenting is not the way. Instead, the “authoritative” parent promotes adaptability, problem-solving, and independence while heavily involving themselves in their child’s life.

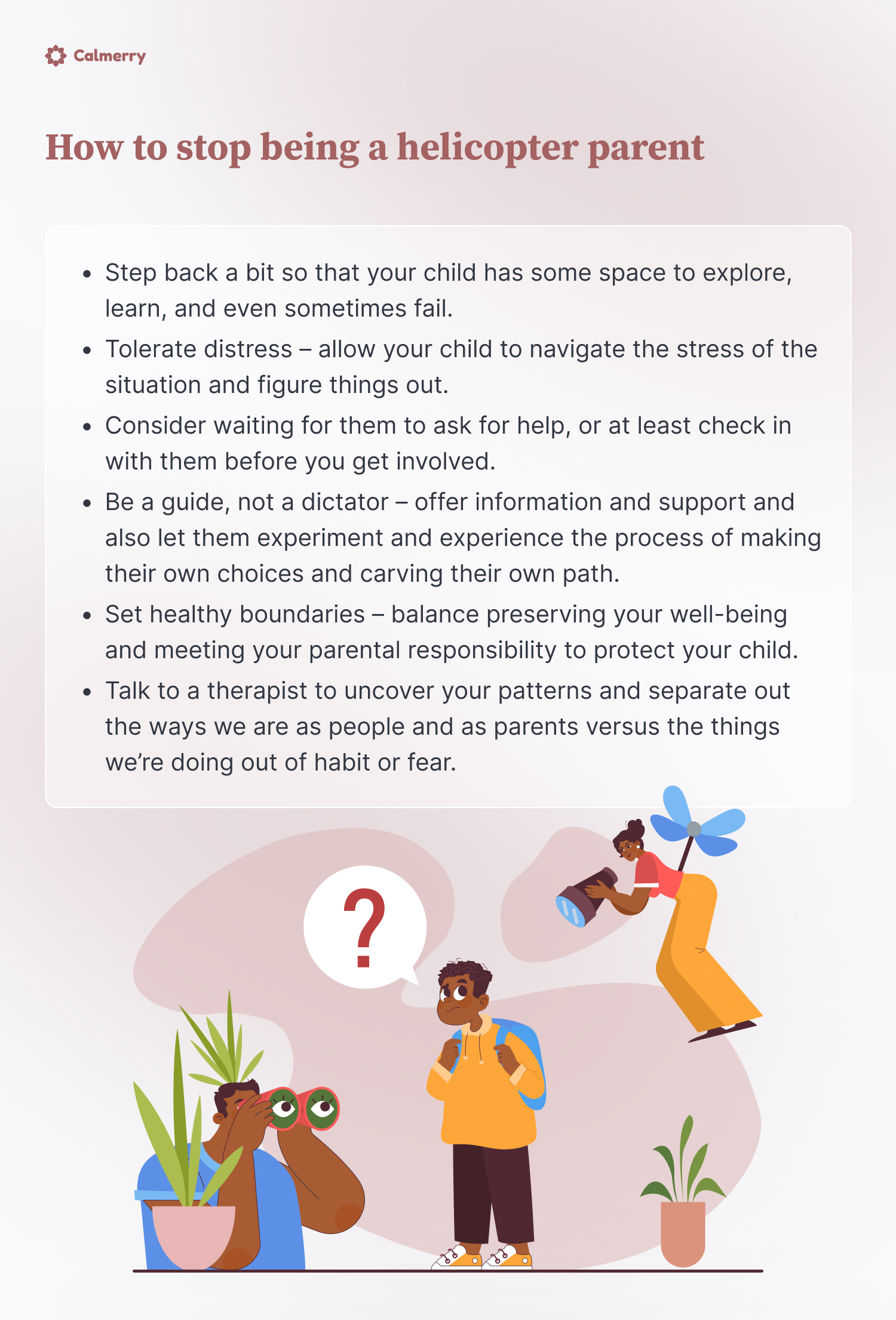

How to stop being a helicopter parent

If you want to stop being a helicopter parent, this doesn’t mean you have to give up all involvement in your child’s life. It’s more about stepping back a bit so that your child has some space to explore, learn, and even sometimes fail.

Here are a few things to try.

Tolerate distress

Whereas a helicopter parent will likely intervene at the first sign of distress, try stepping back for a moment or two while your child navigates the stress of the situation and figures things out.

If your child is old enough, consider waiting for them to ask for help, or at least check in with them before you get involved. This requires a foundation of trust and an open-door policy, so your child feels comfortable coming to you when they need support or guidance.

It also models a healthy response to stress and teaches your kid that, just like you, they can survive heartache and hardship.

– Kate Dubé, Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW)

Be a guide, not a dictator

Much like a guide, a parent who has often traveled the terrain of life has a lot of important insight to share with their kid. You may have ideas based on lessons you’ve learned and can often point your child in the right direction when they get turned around.

But this doesn’t mean you should tell them what to eat, what to wear, what activities to do, who to spend time with, and how to live. Offer information and support and also let them experiment and experience the process of making their own choices and carving their own path.

Set healthy boundaries

Parents create a safe container for their kids – whether it’s emotional or physical safety. Allowing your child to make their own decisions and learn from their mistakes needs to be thoughtfully balanced with preserving their wellbeing and meeting your parental responsibility to protect your child.

A lot of this is about knowing which decisions to leave on the table and which to make yourself. These lines can easily become blurry, particularly if you are struggling with enmeshment trauma.

When it comes to parenting, it might help to think about whether the things you are controlling put your child’s direct safety at risk. A friend of mine would often offer the example of asking her child how he wanted his carrots sliced — in sticks or in medallions, rather than letting him choose to eat cake for dinner instead of vegetables.

– Kate Dubé, Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW)

Talk to a therapist

Therapy is a wonderful place to explore your parenting style and build the relationship with your children that you want to have. For many of us, we get stuck in patterns that evolve from things we’ve learned, observed, and experienced.

In therapy, we can uncover these patterns and habits and separate out the ways that we relate that are true and connected to who we are as people and as parents versus the things we’re doing out of habit or fear.

For some, particularly busy parents, online therapy can break down barriers to accessing the support you need to become the parent you want to be.

A word from Calmerry

If you find yourself in the role of a helicopter parent or if you’re an adult grappling with the effects of such parenting, know that understanding and change are within reach.

Our experienced mental health professionals at Calmerry are here to provide the compassionate support and insight you need.

Jeong, J., Franchett, E., De Oliveira, C. V. R., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021). Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 18(5), e1003602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602

Kouros, C. D., Pruitt, M. M., Ekas, N. V., Kiriaki, R., & Sunderland, M. (2016). Helicopter parenting, autonomy support, and college students’ mental health and well-being: the moderating role of sex and ethnicity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0614-3

How racism can Affect Child Development – Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2023, September 20). Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/racism-and-ecd/

Badger, E., Miller, C. C., Pearce, A., & Quealy, K. (2018, March 27). Extensive data shows punishing reach of racism for Black boys. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/race-class-white-and-black-men

Arlinghaus, K. R., Hahn, S. L., Larson, N., Eisenberg, M. E., Berge, J. M., & Neumark‐Sztainer, D. (2023). Helicopter Parenting Among Socio-Economically and Ethnically/Racially Diverse Emerging Adults: Associations with Weight-Related Behaviors. Emerging Adulthood, 11(4), 909–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968231171317

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

Druckerman, P. (2019, May 21). Opinion | The bad news about helicopter parenting: It works. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/opinion/helicopter-parents-economy

online therapy

live video session