Disenfranchised Grief: Recognizing Unrecognized Grief

In this article

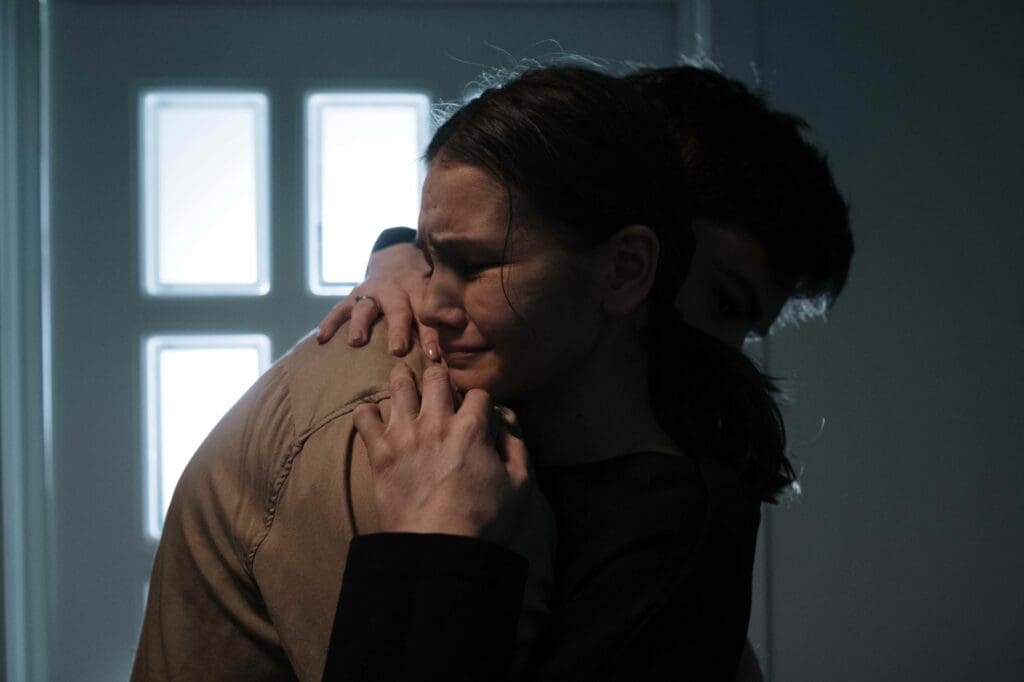

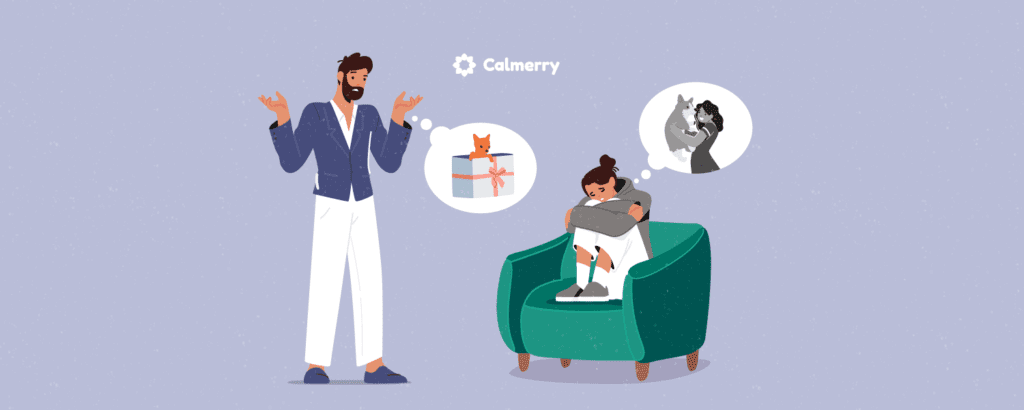

“My mom called me to say that our cat died after a prolonged illness. This heartbroken news made me cry and feel deep sorrow. I was mourning all day long, and my partner, knowing about this, asked me to relax, cheer up, and have some fun.

– I can’t! Don’t you see, I feel awful?

– But why? It was just an old cat! You take it too seriously…

I was hit, having nothing to say. It wasn’t “just an old cat” for me — I lost my best friend, he suffered. I was hurt, and worse than that, my partner rejected my pain.”

The loss of someone or something is one of the most difficult experiences we can face. Grief is always hard. But when our losses aren’t recognized, there’s no one to help carry our grief, we feel isolated, unaccepted, and alone with our pain, it becomes even more challenging.

The story above exemplifies invalidation and the occurrence of disenfranchised grief. Read on to get more examples, learn what disenfranchised grief is, and how to get much-needed support.

What is disenfranchised grief?

The term “disenfranchised grief” was coined by Kenneth Doka in 1989. While this concept explains some aspects of grief, it’s neither a mental health disorder nor a term for a diagnosis.

Disenfranchised grief is grief that can’t be publicly expressed, validated, recognized, and understood by others. A grieving person can’t grieve in the way they need and be vulnerable about their thoughts and feelings around what happened. They can’t show and share their sorrow. Their loss and emotional pain are out of the “grieving norms” established by society.

This empathic failure makes disenfranchised grief often invisible or hidden. It causes a lot of stress and more pain for a person for not being able to heal, adjust, and be supported.

It can lead to negative consequences, such as:

- Complicated grief

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Emotional suppression and numbness

- Social withdrawal

- Substance misuse

- Diminished self-esteem

- Difficulty in forming healthy relationships

- Troubles in coping with consequent losses

Grief is overwhelming. It’s essential to fight the stigma around loss and mental health. Recognizing unrecognized grief can help people create better coping strategies, prevent serious mental health problems, and start the way to recovery.

Disenfranchised grief examples

Some people perceive the death of a relative as the most significant and “true” loss. To many, it “justifies” the scope of difficult emotions we experience and the tears we show. And society sets some “grieving rules” urging not to give great importance to some losses.

So disenfranchised grief can occur after:

- A stillbirth, miscarriage, or the death of a newborn

- Death of a pet

- Loss of a home

- Loss of a job

- Abortion

- Anticipatory grief

- Grieving someone with a severe mental illness

- The transfer of a baby by a surrogate mother

- Major changes in a lifestyle

- Loss of someone who has run away or disappeared

- Death of someone you didn’t know well or never met (a penfriend, a fictional character, or a celebrity)

- Death from substance overdose

- Death from HIV/AIDS

- Loss of a body part

- Loss of hopes, dreams, or expectations

- Loss of an extramarital partner

- Death of an ex-partner

- Death of a same-sex partner

- Loss of a relative you’ve never met

- Death by suicide

- Loss of some important belongings

- Infertility

- Divorce

- Feeling abandoned by a parent or friend

- Ruined relationships

- Death of a patient or client

- Death of someone you don’t remember or who died before you were born

- Grieving that others think is going on “too long”

- Showing “not enough” or “too much” emotions while grieving, etc.

The truth is, no loss is “true” — any loss can be overwhelming. You don’t need to seek legitimization that yours is serious enough to grieve the way you need.

Here are more story-based examples of disenfranchised grief:

“I lost my child a year ago. It was a late miscarriage. My family insists on going on and thinking about happy motherhood in the near future. They think my sorrow after an unborn child is taking too long. But I still feel deep sadness and can’t adjust and accept that it happened.”

“We were a happy same-sex couple. His deadly illness changed our lives. I still can’t tell my family about his death. My pain. Our plans. Us.”

“My brother broke my pocket mirror. “Not a big deal, I’ll buy you a new one!” — said my mom. But it was the only thing left from my dad.”

Why does disenfranchised grief occur? “Grieving rules” that prevent us from healing

Doka defined disenfranchised grief as a type of grief that does not follow socially imposed “rules” about grieving. These “grieving rules” determine, how, who, when, for how long, and for whom a person grieves. Any experience that doesn’t fit the “norm” can remain unrecognized and dismissed.

These “grieving rules” don’t allow a person to share their pain and adequately process their feelings in a way they need and others can do.

When and why does disenfranchised grief occur?

Because the loss is socially unacceptable

People condemn some types of death due to the stigma and ambiguity of the situations. There are some that seem shameful, unacceptable, or uncomfortable to society:

- Suicide

- HIV/AIDS

- Overdose

- Reckless driving

- Accident events due to human factor

- During sex, etc.

Some imagine the usual death of an old person surrounded by close people. Or, quiet death in a dream without any struggles. Or, a military battle in which a person heroically died. Those are examples of “acceptable” losses.

And for many people, it’s so difficult to validate and acknowledge someone’s grief from an “unworthy” or “strange” death. Of course, it’s a matter of bias and stigma.

Because of the loss “hierarchy”

Society doesn’t recognize the loss of some types of relationships as close enough or valid to grieve. We often assume that “canonical” close relationships exist only between relatives and a few friends. And same-sex couples, extramarital partners, ex-partners, neighbors, teachers, colleagues, friends, or relatives, etc., seem like circles of distant acquaintances whose deaths should not greatly impact us.

Even the closest emotional connection with them may be perceived as an unrecognized relationship for grieving. As if they are not enough, there are more important people in our life.

Because of the loss “insignificance”

Unrecognized loss is about insignificance (from others’ POV) of the things that may be of great importance to you.

Society doesn’t recognize that some events can have a significant impact: perinatal loss, death of pets, loss of a body part, diseases that completely change a person’s life, moving in, etc.

This can also show up when the loss involves someone that you had an estranged or contentious relationship with prior to their death or the end of the relationship. There’s an assumption that the nature of the relationship negates or minimizes the experience of grief. Yet sometimes, grief associated with these losses can be even more complicated.

When a griever “isn’t capable” of grieving

“Hey boy, why are you crying so much after your grandfather? You’re only 6 years old. Do you even understand something about death?”

Here, a grieving person is denied the right to grieve because of their age. Disenfranchised people can also be discriminated against for their intelligence, social status, gender, etc. For example:

- Children

- Old people

- People with mental health conditions

- People from other countries/nationalities

- Teenagers in love

As if only mature adults with full legal rights or capacity, can really feel the loss, and everyone else is not capable of deep feelings.

It’s important to note that grief can then be re-experienced as an individual proceeds through various developmental stages and gains a new awareness and understanding through which to process their grief.

Because of society’s expectations of grief

Disenfranchising can also be present in “legitimate” grief if it violates the “rules.” For instance, too long or too short grieving, too intense or almost inexpressible one, with right or wrong rituals, etc.

Society often sets specific rules by which grieving should be carried out. Even a minimal deviation from them may be judged and criticized. This is even evident in company policies where specific criteria need to be met in order to take time off with pay for bereavement.

Disenfranchised grief symptoms: how it feels to have a loss dismissed by others

Grief is one of the most extreme and complicated of all human experiences. It’s normal to experience intense and debilitating symptoms during normal grieving processes. However, surviving loss can be a difficult and lonely experience if you’re struggling with disenfranchised grief.

The symptoms of disenfranchised grief may include:

- The feeling of intense sadness

- Anxiety

- Denial

- Anger

- Numbness

- Problems with concentration

- Physical pain and tension

- Insomnia

- Changes in appetite

- Withdrawal

- Mood swings, etc.

There are some symptoms of disenfranchised grief that a person can experience on top of other overwhelming feelings:

- Guilt

- Shame

- Rumination

- Confusion

- Loneliness

It’s because a person is forced to hide their painful emotions and feelings. They can’t process their experiences and don’t know how to react to a loss under societal pressure.

How does disenfranchised grief affect the healing process?

According to the Kübler-Ross model, there are 5 stages of grief. However, any grieving process is unique.

As part of the natural healing process, you may go through shock, anger, and disbelief. As time goes on, your intense emotional pain begins to lessen. You adjust and accept the reality of your loss, moving on with your life with a renewed perspective. This is considered a healthy healing process.

Disenfranchised grief goes unaddressed and mismanaged. It creates additional difficulties in going through the healing process.

- You can’t use the usual forms of grief expression: for example, you cannot attend a funeral, publicly declare your feelings, wear mourning clothes, etc.

- You face a lack of social support: you can’t get the time off to recover or feel sympathy or compassion from others.

- You’re overwhelmed by intense emotions: you can feel pain, despair, and apathy due to loss, and at the same time, anger, guilt, confusion, and shame concerning your experiences because of social oppression.

- You’re doing an enormous amount of work to suppress emotions: you’re forced to cope with grief inside yourself and not show it because of the rejection of others.

- You have a sense of disconnect from your loss: the result is a feeling of numbness and hollow emptiness that can be felt in all facets of life.

Grief is overwhelming. And disenfranchised grief makes going through this difficult transition even more challenging. Regardless of the reactions of others, it’s important for you to express your feelings as you need it, when you need it, and for how long.

What you experience is real, can’t be argued, and always important.

Disenfranchised grief vs. complicated grief

Complicated grief is when someone continues to experience high levels of distress after a year has gone by since their loss. It causes them significant emotional, mental, physical, and social problems in day-to-day life.

Disenfranchised grief can lead to or contribute to complicated grief and shares some symptoms:

- Intense rumination

- Emptiness

- Isolation

- Depression

- Overwhelming emotions

Moreover, people coping with complicated grieving often feel disenfranchised by society and even their loved ones. Many don’t understand how someone could be sad for so long when the loss wasn’t recent or unexpected.

Disenfranchised grief and ambiguous loss

Ambiguous grief is not uncommon. It’s a type of grief resulting from a non-death loss (a missing person, divorce, adoption, foster care, serious and chronic conditions, disability, incarceration, military deployment, etc.).

In the ambiguous loss, grief becomes unclear and delayed. For example, when a loved one is missing, and there is no body to bury or no way to know for sure if the person is dead. Or when a person is alive and has a severe mental illness. Experiencing constant distress and painful feelings, a griever can’t start a healing process and move on with their life.

Because it often remains unrecognized, the ambiguous loss is more likely to be disenfranchised.

How to support someone going through disenfranchised grief

A disenfranchised griever usually faces challenges related to social support, lack of acknowledgment, and limited help resources. A person may not be given as much time to grieve and may also be denied support from family and friends. Instead, they’re often encouraged to “get over it” and move on. This can lead to anger, isolation, and loneliness.

That’s why it’s important for someone going through disenfranchised grief to know that they are not alone and there is help out there. When we support someone, we should show them that their loss is valid, significant, and worthy of attention and care.

We can support a person going through disenfranchised grief by:

- Offering our love, time, and space to them

- Validating whatever they are feeling

- Listening without judgment

- Understanding the importance of the process

- Sharing our similar experiences or

- Accepting that we don’t know what it is like to go through this type of grief

- Learning about disenfranchised grief and how we might be able to help them heal

- Not pushing them into talking about what happened, unless they want

- Not minimizing their pain

- Offering the type of support they might need

- Encouraging the person to express their feelings

- Allowing them to set the pace of the conversation

- Helping them find a distractive activity if they want

- Advising to seek professional help from grief counseling

Coping with disenfranchised grief

In “socially legitimate” grief, we have many ways to relieve our pain: by organizing and taking part in mourning events and getting social support, help from loved ones, and recognition of our feelings and actions. In the disenfranchised loss, there are no such helping mechanisms, and a griever has to come up with their own ways to cope with the loss.

How can we help ourselves cope with the loss of a loved one? How can we recognize unrecognized grief? There are many solutions, and you should choose what works for you.

Consider the following strategies:

Learn about your kind of loss

Every loss is unique. And every journey of healing is a personal experience. Because most people are unaware of disenfranchised grief or that some types of losses are also losses, the grieving process becomes even more stressful. You may often question whether your experience is valid and fits into the socially accepted norms. These can lead to confusion and self-disenfranchisement.

Know that your grief isn’t strange and out of nothing. And it doesn’t need validation or justification. Learn more about your kind of loss, grief, feelings, emotions, and unique impact on you and others.

Ask the people you trust, social media, and Google. Perhaps, someone shared some similar experiences. Getting in touch with them can help you normalize yours. Of course, you should do such research as long as it’s helpful for you.

Validate your loss and grief

Even if everyone around you dismisses your grief, or you are forced to keep a secret about your loss or relationship with the deceased, you don’t have to accept this. Your loss and your experiences are real. You’re grieving, and it’s valid, even if it seems strange and inappropriate to someone or yourself.

Tell yourself honestly that you are experiencing a loss right now, and something or someone was important to you.

Allow yourself to feel all your feelings and emotions

Treat your experiences and feelings gently. Find a place and time to express and go through them. They may be contradictory and unexplainable to you, but they are real.

Grief is multifaceted and intense. You may feel:

- Helplessness

- Powerlessness

- Anxiety

- Sadness

- Guilt

- Shock

- Shame

- Sorrow

- Confusion

- Anger

- Pain

- Apathy, etc.

All these are okay. Don’t deprive yourself of the right to experience what you’re feeling. The more you deny or ignore these feelings, the longer it will take to move through the healing process.

Revise your present to find a way to adjust

Besides the stress we experience as a reaction to the loss, we find ourselves in new life conditions and have to adapt to them. This is quite an emotionally demanding process during our coping with shock.

Now, you need to adjust. You have to rebuild your life in a new way, move in, acquire new skills, look for other sources of income, get used to life without an object/subject of loss, and find new or give up your hobbies.

Grief is a process that doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens around other events in your life. It’s important to review the current situation to determine how everything around is changing, what is important to do for yourself now, how to move on, and what your needs are.

Practice self-care

Coping with grief is a long road that takes many inner resources. So, it’s especially important to take good care of your mental health, and emotional and physical well-being:

- Be gentle with yourself

- Don’t make any major life decisions right now

- Spend time with some supporting people

- Do what brings your joy and peace

- Sleep and eat well

- Consider going on a trip

- Try not to blame or be hard on yourself

- Spend time outside in nature

- Express your feelings through art or music

- Find a support group or connect with others who are experiencing similar loss

- Reach out to a professional if you have trouble coping healthily

- Set realistic goals and take your time

- Practice mindfulness

- Trust yourself. You can get through this!

Create a mourning ritual

Create your own ritual and set symbols associated with the deceased, especially if you can’t join the official one.

- Plant a bush, tree, or flower in honor of a person

- Light candles on memorable dates

- Carry a remembrance item

- Write the loved one a letter

- Collect significant memorabilia, etc.

Creating mourning rituals helps to “materialize” your grief, make it real to yourself, and maintain an emotional connection with your loved one.

Find a way to talk about your loss and express your grief

It can be a mental health professional, a family member, a close friend, social network pen-friends, a diary that you write your story in, or a letter addressed to your loss.

It may happen that you’re not alone in your situation, and someone has already experienced something similar. You can look for support groups, write a post about your case without additional details, or create a community of disenfranchised grievers yourself.

Practice journaling

It can be difficult to find a person to talk to about how you feel. This is when journaling can be an important tool. Allowing yourself to really feel everything you feel and allowing yourself to be honest about it can help you deal with what you experience.

Journaling can help you move through the grief and find some peace within yourself. It’s a way to release stress and express yourself in ways you might not be able to otherwise. It gives you a place to explain your feelings and thoughts without worrying about who else will judge you.

It can also be a way to take control of your emotions and your life. By writing down your experiences, you can put them in perspective and achieve clarity. Reflecting on how your life roles and identity may have shifted as a result of the loss may provide some insight and meaning as well as unlock the multiple layers that this loss may have created for you.

Journaling to explore the meaning and impact of self-growth and your life can also be helpful when experiencing a loss of a relationship, job, or experience in which there is no physical death.

Get professional help from a therapist or counselor

Many people are stuck with loss because their cultural, religious, and social norms or expectations forbid them from expressing the full measure of their sadness. Therapy can return people their right to grieve as they need.

Disenfranchised grief is debilitating, devaluating, and devastating. But therapy can help regain your power, highlight the importance of your experiences, and move through the healing path healthily.

Working with a licensed grief therapist on Calmerry can help you:

- Recognize unrecognized grief

- Explore your loss and your experiences

- Feel validated and accepted

- Understand why you feel this way

- Get a compassionate, non-judgmental, and safe environment

- Process your painful feelings and emotions

- Get support if you can’t talk about your loss with someone in your life

- Give yourself permission to grieve

- Cope with guilt, confusion, helplessness, shame

- Release the pain you’re holding onto

- Bring the gap between you and your loss

- Gain healthy coping strategies

- Deal with underlying mental health issues

- Cope with or prevent mental health problems that may come from disenfranchised grief

- Learn how to feel better about your grief while feeling calmer about your life

You’re not alone

When we lose someone or something close to us, the only thing worse is feeling like we’re not allowed to be sad. We get enough pressure without the added pressure of society suggesting that we should get over our loss, move on, our loss isn’t significant, or that it isn’t “normal” or “healthy” for us to feel the way we do. That’s what disenfranchised looks like.

This type of grief has a unique impact on a person. They experience all the difficulties expected while coping with grief, but at the same time, they feel as though they have no place to turn for support.

You may feel like you are in free fall, with no hope of regaining your footing. But you’re not alone. Going through grief and processing your emotions and feelings while facing social pressure and stigma is hard work. But healing can come from it. And a licensed therapist on Calmerry can support you in your way.

online therapy

live video session